Space as the Next Battlefield: Bharat’s Evolving Military Space Strategy Post-ASAT

Introduction

In March 2019, a giant leap was made in India’s space defence posture with the demonstration of anti-satellite (ASAT) capability in Mission Shakti. Bharat destroyed a live satellite in low-Earth orbit and thereby joined the very few countries, the US, Russia, and China, that have demonstrated ASAT capabilities. Under the aegis of the DRDO, the launch of this test campaign heralded India’s entry into the high technologies of kinetic space defence.

The test was largely technical but had far-reaching strategic undertones. It put forward a deterrent message and reinforced India’s claim to be part of the worldwide space governance debate. However, according to defence experts, Mission Shakti should not be seen as the culmination, but rather as a beginning in the larger preparation for space warfare. The test revealed India’s vulnerability to satellite attacks, prompting the demand for doctrines to address debris mitigation, satellite hardening against attacks, and retaliatory measures.

Post-ASAT dialogues have involved discussions on space situational awareness (SSA), real-time monitoring, and building international norms. The action put on display India’s aspiration to be acknowledged not only as a spacefaring nation but as one having strategic depth to safeguard its orbital assets. Analysts at ISAS and The Space Review discuss dual-use technologies, the evolution of deterrence theory in the space domain, and India’s cautious preparation in the realm of hard military space infrastructure. The ASAT test, therefore, assumes the form of a geopolitical statement as opposed to a technical achievement.

India’s Military Space Doctrine and Satellite Defence Infrastructure

The emerging Indian military space doctrine broadly incorporates other geostrategic concerns: the importance given to orbital security; the need arising from the threat of space weaponisation. While there is growing dependence of armed forces on the use of satellites for surveillance, communication, navigation, and early warning, the Indian military has integrated space in its strategic planning. The Defence Space Agency (DSA), established in 2019, will further operationalise space-based capabilities for military use, ensuring interoperability amongst services and developing space situational awareness (SSA).

With the deployment of 52 military satellites ranging from electro-optical, radar, to signal intelligence, Bharat intends to enhance its strategic depth. These satellites will be used for secondary empowerment of terrestrial command and control networks for border surveillance and making the country resilient against offensive space operations. This capability is highly required since Bharatis are in the geographic reach of many high-risk flashpoints and counter-space deployments of the Chinese and Pakistani.

Bharat has not overtly endorsed offensive space warfare, doctrinally. Instead, deterrence, strategic signalling, and satellite survivability have been the survey areas of the country. Programs such as Suraksha Chakra and indigenous SSA platforms are under development for tracking space debris, hostile manoeuvres, and high-energy threats. Indigenous production of missile-tracking and counter-jamming technology is jointly pursued with ISRO and DRDO, while the deployment of small sats and constellation redundancies lends a higher level of tactical agility.

Additionally, policy discourse on space security has now become intertwined with global norm-building. Bharath has advocated for a “No First Placement of Weapons in Outer Space” and is actively engaged in discussions about responsible behaviour in space. Thus, Bharat wants to assume a leadership posture as a responsible space power through cultivating a dual-track agenda, technology resilience and diplomatic engagement.

The doctrinal shift is thus neither simply reactionary nor ad hoc; strategically, it matches India’s larger ambition for strategic autonomy and an assertion to become a leading voice on global governance frameworks at the intersection of emerging technologies and weaponised domains.

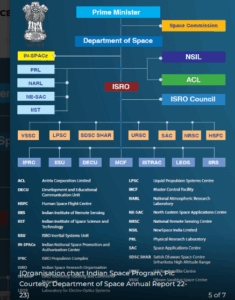

Source (Organisation chart Indian Space Program, Pic Courtesy: Department of Space Annual Report 22-23)

Deterrence vs Diplomacy

India’s approach to space security is deeply anchored in balancing credible deterrence with diplomatic responsibility. As a signatory to the Outer Space Treaty (1967), India’s perspective, the underpinning beliefs for space security, continues to be rooted in a balancing act between credible deterrence and diplomatic responsibility. As a treaty signatory, Bharat propagates the peaceful use of outer space and does not contemplate the placement of nuclear weapons or any other WMDs in orbit around the Earth. This legal and ethical commitment continues to frame its stance even as it develops counterspace capabilities to safeguard national security interests.

Bharat has tried to walk the tightrope between view and act through programs such as Mission Shakti (2019) and kinetic ASAT technologies. As the test signalled deterrence strategically, it operated at low Earth orbit of some 300 km, where debris could decay rather quickly. Bharat demonstrates respect for space debris mitigation through this action, which aligns with the guidelines promulgated by UN COPUOS and the best practices recommended by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC). Bharat introduced restraint and deliberateness by targeting one of its defunct satellites.

Even as technical choices differ, there is a growing voice from Bharat that global norms should be developed to avert an arms race in outer space. It supports initiatives such as the EU-proposed draft Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities and actively participates in the UN deliberations on Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures (TCBMs). Indian proposals often emphasise dual-use technology regulation, responsible behaviour frameworks, and the banning of debris-producing activities.

Bharat promotes, in multilateral forums, the conception of an equitable security architecture so that some form of defensive preparation can exist without prejudicing long-term sustainability. Its space diplomacy argues for inclusive governance, capacity-building for the Global South, and forestalling hegemonic dominance by a single actor.

Ultimately, Bharat positions itself as a responsible stakeholder seeking deterrence to protect assets while championing diplomacy to preserve space as a global commons. This posture not only enhances strategic credibility but reinforces India’s bid for leadership in shaping 21st-century space governance.

Spotlight Feature: Expert Insight

Lt Gen P.J.S. Pannu, “How Space Is the New Frontier of Warfare and Military Strategy,” highlights the rapid transformation of outer space from a passive domain into an active and contested arena of modern warfare. Hence, with technological advancements, space has been increasingly developed as a theatre central to military operations and is no longer merely an afterthought for communication and observation in multi-domain operations (MDO). Space assets provide the spine for worldwide surveillance, precision targeting, missile tracking, secure communications, and navigation. Thus, dominance in space is rightly linked to superiority in the land, air, sea, and cyber domains.

One of the considerations addressed by the article in marking the presence of novel challenges would be the fact that warfare in space was never a traditional military theatre. However, space operations are also awkwardly defined by their orbital nature, with the technologies being dual-use and the absence of codified combat doctrines from long ago. The satellites are not simply used for a singular purpose, the very nature of being in motion all the time makes the dual-use in place and are vulnerable in many ways, from kinetic attacks, jamming, cyber intrusions, and signal spoofing. Such actions can have far-reaching consequences: not only tactically but diplomatically, since disruption to a space infrastructure cascades to several civilian systems such as GPS, communication networks, banking, and weather forecasting.

Lt Gen Pannu explains that the existing strategic framework is not enough to cater to new realities in space warfare. New doctrines, therefore, need to be devised in the foreground of the domain’s complexities, its probable irreversible damage, and political implications. Issues such as differentiating civilian satellites from military ones, the implications of anti-satellite or ASAT weapon tests, and space debris build-up require a global, long-range approach. A single kinetic attack can produce debris that threatens all space-faring nations for decades. On the same note, jamming or cyberspace attacks on satellites generate cascading failures in the critical systems on Earth.

First, space warfare needs to be institutionalized within Indian military planning, training, and strategic doctrines. This should include the crafting of a single space warfare doctrine that fits within the multi-domain operational concept. Secondly, the military and the political leadership should realize that control in space equates to leverage on Earth; hence, command and control structures need to reflect that reality. Last, international co-operation must grow, and global norms need strengthening that govern military conduct in space. Treaties such as the Outer Space Treaty need to be updated to cover militarization and possible weaponization of space.

On equal terms, Lt Gen Pannu reiterates that space has become the critical battlefield of the 21st century. Winning future wars will depend on how well a nation integrates space into its broader military strategy. As boundaries are blurred across domains, and with adversaries furthering their space capabilities, Bharat and other space-faring nations will have to answer this call by investing in technology, developing worthy doctrines, and diplomatically forging the future rules of engagement in the last frontier.

Conclusion

Presently, India’s having its space defence journey pivots on three essential facets: the enhancement of Space Situational Awareness (SSA), development of inter-service space warfare education, and AI integration into decision support Systems for real-time. These are some drastic changes from reactive space asset protection to their strategic deterrence. The call is that Bharat must ensure deep indigenous innovation, doctrinal clarity, and shared expertise to stand up as a global space power.

To appreciate the urgency of the matter with a sense of foresight, Vice Admiral (Retd.) Ajit Kumar, ex-Chief of Integrated Defence Staff, said: “In tomorrow’s wars, space will be the first frontier and the final arbiter. India must command it, not just navigate it.”

To keep the wheel turning, defence professionals, scholars, and technologists are invited to participate in the next set of ISSS webinars and roundtables on “Orbital Combat Doctrine” and “AI in Military Space Ops.” These forums are designed to stimulate multidisciplinary discussion, grow academic-industrial collaboration, and set a strategic roadmap for Bharat in orbital deterrence and beyond.

References

- Lele, A. (2023, March 27). Indian ASAT: Mission Shakti should be a comma, not a full stop. The Space Review. https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4556/1

- Pannu, P. J. S. (2025, January 11). How space is new frontier of warfare and military strategy. DRaS. https://dras.in/space-new-frontier-of-warfare-and-military-strategy/

- Press Information Bureau. (2024, April 19). Cabinet approves Indian Space Policy 2023 to enhance role of Department of Space. Government of India. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2068184

- Rajagopalan, R. P. (2023). India’s space ambitions and the future of arms control in outer space. Journal of Strategic Studies, 46(4), 628–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/14777622.2023.2277253

- SIA-India. (2024, April 14). Harmonizing military space ambitions with India’s national space strategy: A comprehensive analysis. Indian Aerospace & Defence Bulletin. https://www.iadb.in/2024/04/14/harmonizing-military-space-ambitions-with-indias-national-space-strategy-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Department of Space. (2023). Annual report 2022–2023. Government of India.

- United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). (n.d.). Space debris mitigation guidelines. https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/topics/space-debris.html

- Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee. (2007). IADC space debris mitigation guidelines. https://www.iadc-home.org/documents_public/view/id/77#u

- European Union. (2014). Draft code of conduct for outer space activities. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu_code_of_conduct_for_outer_space_activities.pdf

- Ministry of Defence. (2019). Establishment of the Defence Space Agency (DSA). Government of India.

- Kumar, A. (2025). In Space as the next battlefield: Bharat’s evolving military space strategy post-ASAT [Expert quote].