Dr. Shelly Gupta has been teaching economics at Delhi University as an Assistant Professor for past one decade.

Abstract

The turn of the new century witnessed India significantly expanding its development assistance, both in terms of volume and diversity, thus, transforming itself into a donor. Today, India has become recognized as the new pole of growth in the world economy. While having a large amount of poverty and hunger in its own country, it contributes to the development of other nations in need. As a result, they prefer to be referred to as “development partners” rather than “donors”.

While India’s assistance distribution has climbed to levels equivalent to many smaller industrialised nations, this data is not comprehensibly available. Because India along with other major southern donors, does not report its data to the OECD, the phenomenon of India‟s foreign aid remains little recognized and appreciated. This paper tries to make an important contribution to identifying India‟s approach to the development assistance program. This paper will examine the positioning of India in the international development assistance framework, which transforms its status to an emerging donor, in the broader context of how the form and scale of India‟s development assistance influence the total scope of overall international aid.

Keywords: Foreign Aid, India, Development Cooperation, Bilateral Assistance JEL Codes: F35, P33, P45

Background

Many developing and underdeveloped nations have relied on inflows of external resources to bridge the domestic saving-investment gap and the import-export gap. These flows are considered vital as they bring with them a skilled workforce and technical knowledge.

In the past, countries such as Greece, Taiwan, Israel and the Philippines have shown rapid growth based on investment financed mainly by external assistance in the form of grants and

loans. Aid thus was supposed to help developing economies utilize their resources more efficiently and in a fuller way to accelerate growth. However, this external assistance flowing mainly from rich nations to poor nations was gradually becoming an instrument of foreign policy to control the weak nations and create an environment in which they could pursue their own social objectives. Griffin and Enos (1970) in their article, mention that “favors granted are favors asked” and “not all aid assists”. Foreign aid coming from the developed nations may not always improve the well-being of the nations and may deter growth rather than encourage it.

In the light of the foregoing viewpoint, together with the well-documented fact that the developed countries were never able to achieve the targeted rate of 0.7% of GNI as ODA (Official Development Assistance) to developing countries, this gap was compensated by foreign aid from the developing economies. Several developing nations began contributing to the development of their peers via development assistance. These donors are frequently described by the terms “new,” “emerging,” “non-traditional,” and “non-Western” donors. Southern donors‟ dual role as aid providers and recipients sets them apart from traditional (Northern) donors. While these nations are themselves not wholly developed and still struggle with poverty and hunger, they are determined to help other developing countries escape poverty and underdevelopment.

There has been a growing amount of aid flowing from middle-income and transition economies strengthening South-South partnership and cooperation. Although obtaining an exact figure is difficult because these donors lack a standardised method of reporting their developmental flows, the available data suggests that non-DAC donors (which include small donors such as the UAE, medium donors such as Korea and Turkey, and large donors such as China, India, and the United Arab Emirates) provided approximately 15% of total aid flows in 2019. India‟s international development cooperation has been rising every year and totaled USD1.6 billion in 2019.

India is significantly extending its development cooperation framework from one of the highest recipients of aid to one of the largest donors of aid among developing nations. These emerging nations provide technical and budgetary assistance to other developing countries to improve their economic and social well-being. India’s development partnership model incorporates SSC (South-South Cooperation) in its approach to development, which is based on mutual respect, shared benefit, and long-term sustainability. It gives unconditional assistance based on the development partners’ objectives1.

In this paper, we will look at India’s position in the global development assistance framework and determining how it contributes towards strengthening SSC and overall global development2.

Fundamentals of India’s Development Cooperation

While some literature points to India as an emerging donor (Six,C. 2009), it is not really the case. India has long been a provider of development assistance (since independence) to its neighboring nations. Starting from the Colombo Plan in 1950, India was one of the largest donors of technical assistance among all the participating nations of South and South-East Asia, followed by various other projects like the Mekong river project in Cambodia and the Special Commonwealth African Assistance Plan3. India was also giving out aid to countries like Nepal and Bhutan, which continues even today (Mukherjee, R. (2015)). It is worth noting that India has been administering these assistance packages despite having own 269.8 million people living in poverty in 2011-124 and battling other socio-economic problems too.

India‟s policy towards development cooperation has been the responsibility of the Ministry of External Affairs. It has echoed the spirit of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” in several of its annual reports and outcome budgets5. Inspired by Gandhiji, the term means that the “World is One Family”, suggesting that India is committed to promoting international peace and harmony by

- https://mea.gov.in/Overview-of-India-Development-Partnership.htm and This underlying SSC philosophy has also been stated in a Keynote address by Foreign Secretary (para 7) at Conference of Southern Providers- South-South Cooperation: Issues and Emerging Challenges on April 15, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.mea.gov.in/SpeechesStatements.htmdtl/21549/Keynote+address+by+Foreign+Secretary+at+Conference+of+Southern+Providers+Sout hSouth+Cooperation++Issues+and+Emerging+Challenges.

- Note: This analysis is limited to bilateral assistance only

- Speech Of Shri Morarji R. Desai Minister Of Finance Introducing The Budget For The Year 1962 -63 (Interim), p.4, Para 13.

- https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=15283

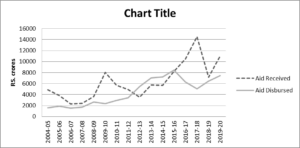

- The phrase is mentioned in MEA Annual reports of 2020-21, 2019-20, and 2018-19 and in various MEA outcome budgets as well. sharing its limited resources. The sentiment was also reverberated by Jawaharlal Nehru, the then Prime Minister of India, in his Constituent Assembly address on 15th august 1947 as- “Let us help ourselves” encapsulates the vision that India had for “what it wants to be” and “what it wants the world to become”. These statements align with the Indian policy of non-alignment and South-South solidarity. Thus, following these approaches, the Indian government has undertaken strategic initiatives such as the “Neighborhood First policy”, “Act East” policy, “Focus Africa”, “Focus LAC”, and “Focus CIS”, among others7. The Indian government has also made clear its stance through various statements that its assistance will be non-conditional in nature and guided by the terms and conditions of the partner country such that it harnesses its potential. The principle of non- conditionality is supplemented with principles of non-interference and mutual respect and benefit8. These principles are believed to be drawn from the Panchsheel agreement (Katti,V., Chahoud,T., & Kaushik,A., 2009) , later incorporated into the Bandung Principles. India seeks to maintain strong, cooperative, and mutually beneficial relationships with other developing nations. India‟s development cooperation policy has been at the forefront in achieving these objectives. India has provided aid depending on the needs and priorities of the partner nations, in accordance with the principles of non-conditionality. India has a long history of development assistance and the figure below shows a comparison of India’s development assistance received and disbursed over the last fifteen years. The analysis shows how India transitions from being a recipient initially to a donor of development assistance in the intermediate years of our analysis. Thus, India‟s aid spending outweighs the amount of aid it receives. Figure. Aid Received9 and Disbursed10 by India, 2004-05 to 2019-2011

- https://mea.gov.in/Overview-of-India-Development-Partnership.htm

- https://www.eximbankindia.in/blog/blog-content.aspx?BlogID=12&BlogTitle=South- south%20cooperation%20&%20trade

- https://mea.gov.in/Overview-of-India-Development-Partnership.htm

- Aid received consists of net bilateral loans, multilateral cash grants and commodity grant assistance

- Aid disbursed comprises of bilateral loans and bilateral grants.

- Because the entire grant/loan ratio is modest, including multilateral grants (rather than bilateral as taken throughout the entire study) in the case of aid received will not have a substantial impact on the overall study.

Source: Various Union Budgets and MEA Annual Reports

India is investing in a lot of developmental projects in the areas of infrastructure, power and energy transmission, skill development and others in the neighborhood countries of South Asia, in alignment with its „Neighborhood First‟ initiative. Simultaneously, it is investing in improving cross-border connectivity in order to better link north-eastern states to the rest of the world and boost growth in those regions. The issue of regional connectivity has also been addressed by the bilateral and multilateral donors to India, where they have predominantly focused on improving transport infrastructure and thus taking a step towards removing trade bottlenecks, which act as an impediment to progress. At the same time, there is enough focus on capacity building and skill development of labor by India through its training programmes (under ITEC). As a result, India’s development cooperation fosters both physical and people infrastructure. However, this does not eliminate the challenges that are faced by India.

The development cooperation framework necessitates coordination between many ministries at various levels which poses a challenge for the economy. A central agency might potentially cut administrative costs while also increasing transparency in the process (Purushothaman, C. 2021). Aside from that, India must ensure that the development flows it receives are non-extractive and do not hurt local resources or local people. This is critical for inclusive growth to prevail.

India, through its development cooperation framework, is contributing to the South-South development Cooperation and carving out a position for itself in the global South.

List of References

Agrawal, S. (2007). Emerging donors in international development assistance: The India case. Chaturvedi, S., Chenoy, A., Chopra, D., Joshi, A., & Lagdhyan, K. H. (2014). Indian development cooperation: The state of the debate (No. IDS Evidence Report; 95). IDS.

Katti, V., Chahoud, T., & Kaushik, A. (2009). India’s development cooperation-opportunities and challenges for international development cooperation. Briefing Papers, (3/2009).

Manning, Richard (2006), “Wi l “Emerging Donors” Change the Face of International Cooperation”, Development Policy Review, 24(4): 371-385.

Mukherjee, R. (2015). India‟s international development program. The Oxford handbook of Indian foreign policy, 173-187.

Mullen, R. (2014). IDCR report: the state of Indian development cooperation, p.3. Indian Development Cooperation Research.

OECD (2012), From Aid to Development: The Global Fight against Poverty, OECD Insights, OECD Publishing, p.3.

OECD-iLibrary,Development Cooperation Profiles- India. Available at https://www.oecd- ilibrary.org/sites/18b00a44-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623- en&_csp_=b14d4f60505d057b456dd1730d8fcea3&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter&

_ga=2.167681595.485820837.1625468128-1526753300.1620141746#section-d1e64805

Price, G. (2004). India’s aid dynamics: from recipient to donor?. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, p.5.

Tilak, J. B. (2016). South-South cooperation: India‟s programme of development assistance– nature, size and functioning. In Post-Education-Forall and Sustainable Development Paradigm: Structural Changes with Diversifying Actors and Norms. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p.311.