Introduction

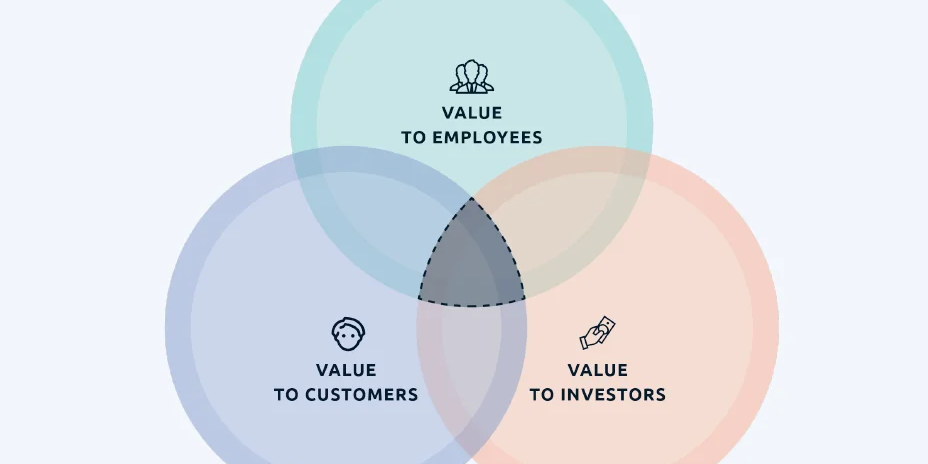

As the focus is on investment and employment, there has been a sharp rise in interest in the results of applying insolvency rules and regulations. The attitudes of the legal system are reflected in how bankruptcy is handled in an economy. Insolvency laws are predominantly based on local systems and practices. Considering the importance of such reforms, it must be sensitive to local conditions. As per the preamble of the IBC, its twin objectives are to maximize the value of assets and promote entrepreneurship in a time-bound manner while balancing the interests of all stakeholders. Note that handling financial and business or operational distress have a major effect on investors’ confidence, which in turn significantly impacts the availability of investment and the cost of capital, which drives economic growth. This article’s focus is not to discuss value maximization and entrepreneurship promotion from the prism of pro-creditor and pro-debtor. This article’s thrust is to review the extent to which the objectives of the IBC have been achieved based on the IBC-related data. In this context, we need to understand the five pillars of bankruptcy in India:

- the IBC,

- the regulator (IBBI),

- the practitioners,

- NCLT/NCLAT/courts, and

- the culture

We will see in the later part of this article that each pillar plays a role and contributes to the success or failure of the system. In addition, three fundamental goals are generally set for any insolvency law: transparency, predictability, and efficiency. Although improving transparency is an ongoing process, the IBC mechanism based on rules and regulations prima facie appears transparent compared to earlier, but at the stage of implementation, the issue related to compromised transparency is apparent whether it relates to the appointment of select Resolution Professionals (RP)/Interim Resolution Professionals (IRP) or Valuers or Advocates. Predictability, which is closely related to transparency, and efficiency are the ones that are more visible and hence attract more attention. The efficiency of a bankruptcy regime depends not only on its formal rules, regulations, and procedures but also on who implements them in practice. A lack of transparency, predictability, and efficiency increases credit costs, delays the process, and harms the value of assets. The efficiency of the IBC can be tested based on a number of “good business, bad balance sheet” companies that were rescued.

Critics are raising two issues regarding the IBC. The first issue concerns the average delay in completing the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP), which is 671 days for resolved cases and 486 days for liquidation. The second issue is lower realization rate of approximately 32% of the total claims for cases where CIRPs have been resolved and approximately 7% of the claims in cases where CIRPs ended in liquidation. Before we devolve on these matters and the objectives of the IBC, it would be necessary to review data related to the IBC in detail and draw inferences that would be used for further improvement in the system.

Rising Delays in the CIRP Completion

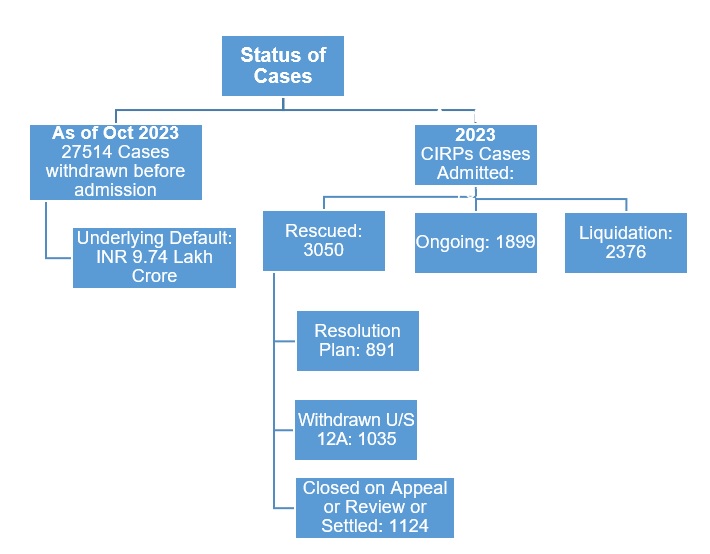

Four parties can initiate CIRP: financial creditors (FC), operational creditors (OC), corporate debtors (CD), and regulators like the RBI in the case of financial service providers (FSP). The status of cases withdrawn before admission under CIRP and after admission on a total basis ( Table 1) and based on the initiator of the CIRPs ( Table 2) is depicted below.

Table 1

Table 2

| FC | OC | CD | FSP | Total | |

| No of CIRPs Admitted | 3300 | 3586 | 435 | 4 | 7325 |

| Percentage of CIPRs Admitted | 45.05% | 48.96% | 5.94% | 0.05% | 100% |

| Average Time Taken for Closure of CIRPS | 677 | 686 | 569 | 632 | 671 |

| Average Time for Liquidation | 497 | 492 | 414 | – | 486 |

(Source: The Quarterly News Letter of the IBBI; Oct-Dec 2023)

The Reality of Rising CIRP Completion Time

The OC, which accounts for approximately 50% of the admitted cases, dominates along with the FCs in the IBC system. An underlying default was less than INR 1 crore in 80% of the CIRPs initiated by the OC. It appears that the IBC system is being used as a tool for recovery, and the system is clogged with cases that are primarily like contractual disputes between parties. The withdrawal statistics support this proposition: more than 27500 applications with 9.74 lakh crore default amount were withdrawn before admission. Even in cases admitted under CIRP, approximately 30% of cases are either withdrawn u/s 12A or closed on appeal/ review/ settled. The CD in such cases was not a candidate for bankruptcy, but the IBC system was used to resolve contractual disputes. This consumes significant time for NCLT, which is one of the key pillars of bankruptcy. Even after admission, of 7321 cases, 1034 were withdrawn, and in most cases, settlement took place between parties. A more granular review indicates that out of 1034 cases, 55% relate to less than INR 1 crore, approximately 75% to less than INR 10 crore and more than 90% relate to less than INR 50 crore. Approximately 50% of cases are from the OC. This indicates a separate CIRP process is needed for small cases up to INR 50 crore to be done through IBC small cases, and it should be simple, speedy, and cost-effective.

In 891 cases where a resolution was approved, the average time taken was 671 days. It appears that withdrawal cases pre and post-CIRP are consuming more time as compared to deserving cases. Therefore, the cases that need more attention and scrutiny have a shorter time, and this could be one of the reasons for delays. An analysis of the dispersion of the admitted cases by sector has remained almost the same when data for December 2022 and December 2023 are compared. The manufacturing sector accounts for the highest share at 38% of the total cases, followed by the real estate sector ( 21% ) and construction (12%). This indicates that more than 1300 companies, out of the ongoing 1900 companies, belong to the large employment-generating sector. Several real estate companies’ projects are viable but still stuck in the IBC for reasons that are apparent but not cured and in this affecting the lives of lakhs of homebuyers. The above statistics confirm that rescue is adversely affected where attention is due the most and the delay despite the rise in the NCLT benches is a cause for concern and needs to be addressed.

Out of close to 1900 ongoing CIRPs, there has been a delay of more than 270 days for the completion of the process of 68% of ongoing CIRPs in December 2023 as compared to 73% in December 2021 and 64% in December 2022.

Lower Resolution and Higher Liquidation -What’s the True Picture?

As highlighted in Table 1 a lower resolution and higher liquidation prima facie indicate inefficiency in the IBC system. However, this is not the true story. The reason for the lower rescue can also be traced to inadequate bankruptcy planning, or the tendency of the companies to wait until it is too late to rescue or old BIFR cases, and to that extent, the IBC system itself can not be held responsible. To a large extent, creditors are also responsible for delaying the admission process. Identification of the Twilight Zone is important for value maximization. The number of cases ending with resoltions vs the number of liquidation cases has increased from 0.21 in FY 2017-18 to 0.64 in Q3 FY 2023-24. This indicates some improvement in rescuing companies. Out of the admitted cases, companies that have been ordered for liquidation 77% pertain to BIFR cases and /or defunct companies. Simply stated, the scope for rescue of such companies was limited.

Tweak the Existing System to Promote Entrepreneurship

The share of CIRP by CD has been declining over the years. Only approximately 6% of CIRPs have been initiated by the CD. Such a low level of CD-initiated CIRP does not support that IBC has been able to promote entrepreneurship. The CD, it appears, is afraid to approach the IBC system because of fear of losing control, social and cultural stigma, the negative impact on borrowing powers, and the lengthy and costly processes. The main reason for this, it appears, is the loss of control. In the Indian system where most companies are people-driven and hence a loss of control generally results in value destruction. Restructuring by banks is therefore more preferred option. An assumption that all business failure is the result of incompetence, recklessness, or even fraud is not right. For example, under US Chapter 11 bankruptcy, it is easy to access for the debtor, who generally has to file a petition with the court disclosing certain financial and other information. However, a court order is not needed to activate the process, and there are no other onerous conditions to be fulfilled. This promotes entrepreneurship and encourages timely access to the bankruptcy system. No doubt that the IBC has disciplined the debtors, especially those who were Wilful defaulters, noncooperative borrowers, or were involved in fraud. This can be considered as phase 1 of the IBC. Now in phase 2, the focus should also be on promoting entrepreneurship. Assuming that the IBC mechanism is a hospital, early access by management affected by the vagaries of market conditions would help in the survival of the business. Businesses that are injured by the mistake of the management can be forced into hospitals by the FC or the OC on a timely basis if there is predictability and efficiency in the system. The rights of entrepreneurs, workers, and creditors must be properly balanced if an economy is to reach its maximum potential, and it should not be tilted in one way. An incompetent or fraudulent management should be replaced by new management who can better use the resources. But if an entrepreneur is unlucky, s(he) should be given a second chance. For example, Singapore has allowed the transplant of US Chapter 11 bankruptcy provisions although with modifications. This is in sync with the recent trend of adopting best practices within the existing bankruptcy system. There may be skeptics who would be averse to this idea. But considering the constituents of the committee of creditors (COC), their experience of running businesses, and their objective of control, it is clear that they are focused on recovery. Instead of people of experience, judgement, and oodles of common sense, those who participate in the COC generally lack experience in running a business and are more focused on recovery. Also producing consensus among creditors, many with different agendas, is akin to herding cats. Certain areas of the existing IBC system, which affect delays and have adverse impact on the asset value need immediate attention.

- Why should a company on a deathbed move gradually from rescue to liquidation and require both fair value (going concern value) and liquidation value (gone concern value)? A bankrupt company may be either economically efficient or inefficient. Only efficient companies should be selected for rescue for inefficient companies the best option is liquidation.

- Why should there be less focus on running the business and more focus primarily on compliance?

- Does the combo of RP/COC function as a board for rescuing a company? The role of COC should be the same as the boards of directors of public companies. The RP/COC should not use the system for personal gain at the expense of other claimants and stakeholders.

- Why should there be a significant time gap between approval by the COC and NCLT?

- Shouldn’t there be the concept of rescue and support deserving cases the penalty?

- Shouldn’t there be a system for screening companies(operationally distressed or financially distressed or both ) based on their existing financial parameters and prospects about rescue or liquidation?

- Rather than replacing existing management with external one (a combo of RP and COC) in each case there should be a court-monitored board consisting of existing management to rescue the company, especially for companies where existing management has not duped the system and there is substantial enterprise value.

- How many RP are turnaround specialists or have expertise in running a business or the COC is ready to fund such specialists to avail their services?

- Either the technical member of NCLT should ideally have a background in valuation or it should have the option of appointing a valuation expert to assist in the valuation matters. The appointment of qualified valuation experts will not necessarily solve all the matter. The value conclusion of RP-appointed valuers needs to be tested.

Falling Realisations from the CIRPs

It is also important to note that maximizing the recovery of creditors is not necessarily the same thing as maximizing the future viability of the entire enterprise. Typically, the value of assets decline with time if distress is not addressed on time. However, this also depends upon the type of assets. For example, the value of land and investment made by the bankrupt firm may not decline and are typically independent of bankruptcy. The delay however hurts assets like trained employees, customer base, and intellectual property because these are assets that are easily damaged by intervening bankruptcy. The overall realisation for creditors till December 2023 where CIRP cases have been resolved is 32% of the claim amount as shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3

| Total Claims | Fair Value of Assets | Liquidation Value of Assets | Realized Value |

| 10.07 lakhs crore | 2.97lakhs crore | 1.90 lakhs crore | 3.21 lakhs crore |

Table 4

| FC | OC | CD | FSP | Total | |

| Realization as % of Claims | 33.8 | 18.7 | 17.9 | 42.4 | 31.9 |

The average liquidation value (gone concern value) is at a 36% discount from the fair value (going concern value). This is not surprising considering the estimation of liquidation value from the value using a standard discount of 30 to 35% without giving cogent reason and a detailed analysis of the case. A higher realized value than even fair value looks like better performance. But this could be either because of lower fair value or because of a rise in the value of some assets due to a delay in resolution. The fair value below 30% of the total claim shows that the fair value estimate is based on existing status and not on restructured basis. The reason for this appears to be the flawed definition of fair value and summation of the value of assets mainly classified into land and building, security and financial assets, and plant and machinery. The fair value definition requires the valuer to assess “ the realizable value” which technically means transaction costs should also be reduced from the estimated value which is inconsistent with the purpose for which it is estimated. The definition of fair value used in IBC is the definition of Market Value defined by the International Valuation Standard (IVS) except the words “ the realizable Value”. The sum of parts value in most cases is below the whole (the enterprise value). The recovery motive of the COC, selection of self-serving valuers, lack of scrutiny of the valuation reports, and personal gain of other parties are also key factors . The creditors have realized approximately 168% of the liquidation value and 86.5% of the fair value ( based on 783 cases where data for fair value are available). The haircut for fair value is 14% based on the fair value and 68% based on the admitted claims. These realizations do not include the CIRP costs and future realizations like equity. It appears that current realization would be even lower if data relating to early IBC cases were excluded when realization was high. The average realization for liquidation cases is just 7% of the total claim. Out of liquidation cases, 43 cases have sold as a going concern. Several factors affect the realization. However, key factors for lower realization can be traced to factors like delayed admission,

Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process (PPIRP)

PPIRPs which have been operative since April 2021. It seems it has not yielded the desired result. Till December 2023, only 7 applications were admitted. Out of 7, 5 cases were resolved, one case was withdrawn, and one case is ongoing. The key attraction of PPIRP is the speed. The benefits of speed are supposed to minimize erosion in value while maximizing return to creditors and in the process rescuing the business and preserving all or some of the employees’ jobs. However, PPIRP has not picked up as expected.

Summary

The IBC regime has indeed helped in rescuing companies out of the clutch of rouge promoters. The fear of losing control has helped parties recover their dues. However, a longer-than-prescribed time in completion of CIRP is a cause of concern. More than 70% of the ongoing cases are in the employment-generating sectors like manufacturing, real estate, and construction. As a result of this value maximization objective is defeated. Also factors like late arrival in the CIRP, recovery motives of COC and interplay by practitioners result in lower recovery. Without a tweak in the existing system, objectives related to promoting entrepreneurship cannot be achieved.